Understanding Grasslands: The Role of Increasers, Decreasers, and Rangeland Health

Understanding Grasslands: The Role of Increasers, Decreasers, and Rangeland Health

Native rangelands are celebrated for their rich biodiversity, often highlighted by the presence of hundreds of plant species from grasses to sedges, forbs, and even shrubs. This diversity is what helps these rangelands stand the test of time and creates a resilience that is nearly impossible to replicate or mimic. When we take a closer look, the land will tell us a story. This story gives us insight to management and environmental pressures that affect the overall health and viability of the grasslands. Taking time to learn some of the common plants that grow in your pastures can help ranchers evaluate their range health.

It can take a while to get the hang of identifying the different plants in your pasture, but even having a general idea of what’s out there can give you some great insight into how your pasture can be used and what it’s capable of. Identifying and then further understanding the qualities of each plant can help to gear your management decisions in order to keep your pastures as healthy as possible.

Once plants are identified, we can classify them in certain categories depending on their response to grazing. They can be classified as either an increaser, decreaser, invaders or exotic invader. Plants that decrease in abundance with improper grazing are Decreasers (D). Plants that increase in abundance under similar management are Increasers (I). Plants that invade sites or heavily increase on sites with improper grazing are Invaders (IV) and lastly, plants not native to North America are deemed exotic invaders (EIV).

Decreaser species are plants that struggle when faced with disturbances like overgrazing, fire suppression, or the invasion of non-native grasses. These plants are generally more sensitive to environmental changes and will start to decrease in abundance after a period of heavy disturbance. Native grasses like Western Porcupine Grass or Northern Wheatgrass are classic examples of decreasers and are slower to recover from frequent or heavy grazing pressure.

On the flip side, increasers are species that tend to thrive when rangelands are under stress, particularly as the more sensitive decreaser species are reduced or disturbed. When these plants dominate, it often comes at the expense of other potentially more desirable native species. As increasers increase in abundance, biodiversity declines, and the balance of the grassland ecosystem is disrupted. This shift in plant composition can lead to a loss of habitat for wildlife that rely on those native species, further affecting the entire ecosystem.

When a pasture is grazed too hard for too long, the plant community starts to shift. You may begin to notice fewer of the grasses and forbs you would normally see and then over time, the different layers of vegetation, such as club moss, mid-height plants, and taller grasses, can start to disappear altogether. This creates gaps in forage quality, reduces overall productivity, and opens the door for less desirable species, often the increasers and invaders, to take over.

Each rangeland is unique, from the soils to the climate, topography and the way they are grazed. When we assess range health, we look at what kind of plant community and structure we’d typically expect for that specific region and ecosite. If what we see on the ground looks a lot different from that expected mix, it can be a sign the land is under stress or not functioning the way it should.

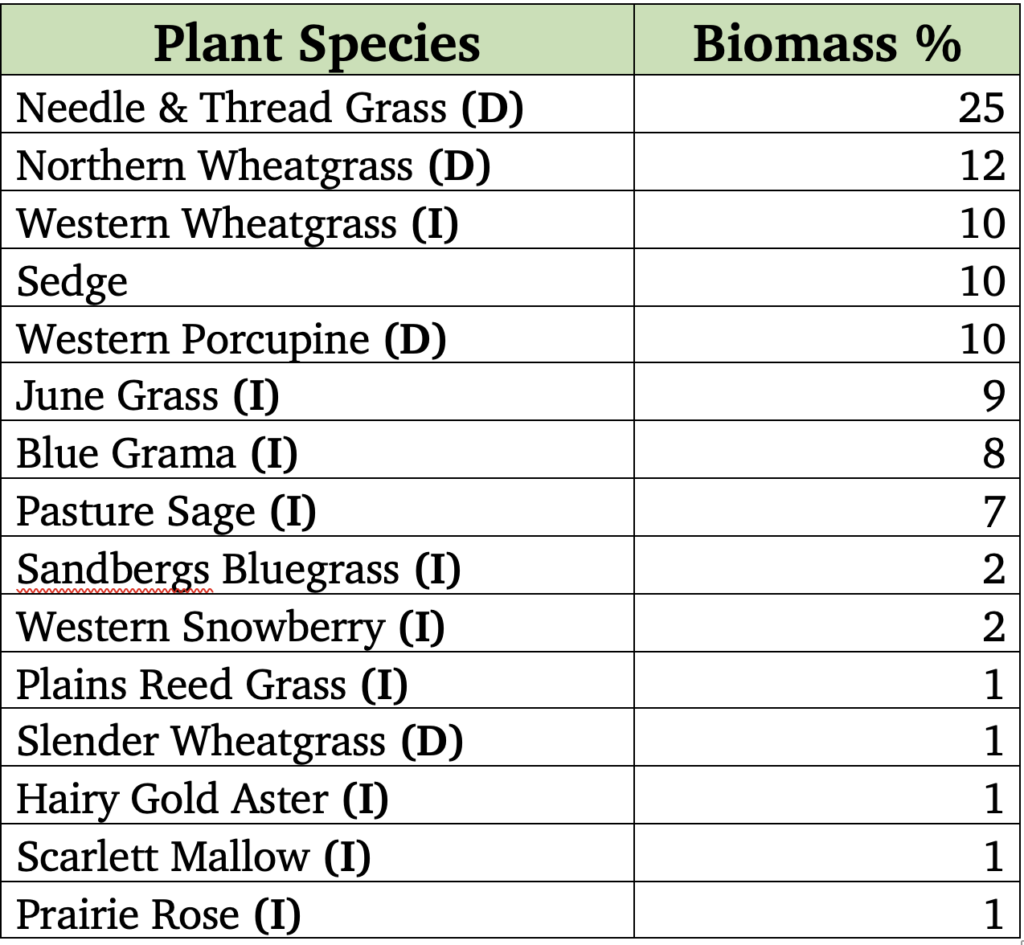

Here is an example of what we might expect to find on a sandy loam ecosite in the dry mixed grasslands.

This site closely resembles what reference plant community looks like for this ecosite. In this ecosite we also found all the plant layers were present. Native grasslands should have a mixture of mid grasses, short grasses, shrubs and forbs present but if one or more of these layers are missing it indicates a problem or stress on the rangeland.

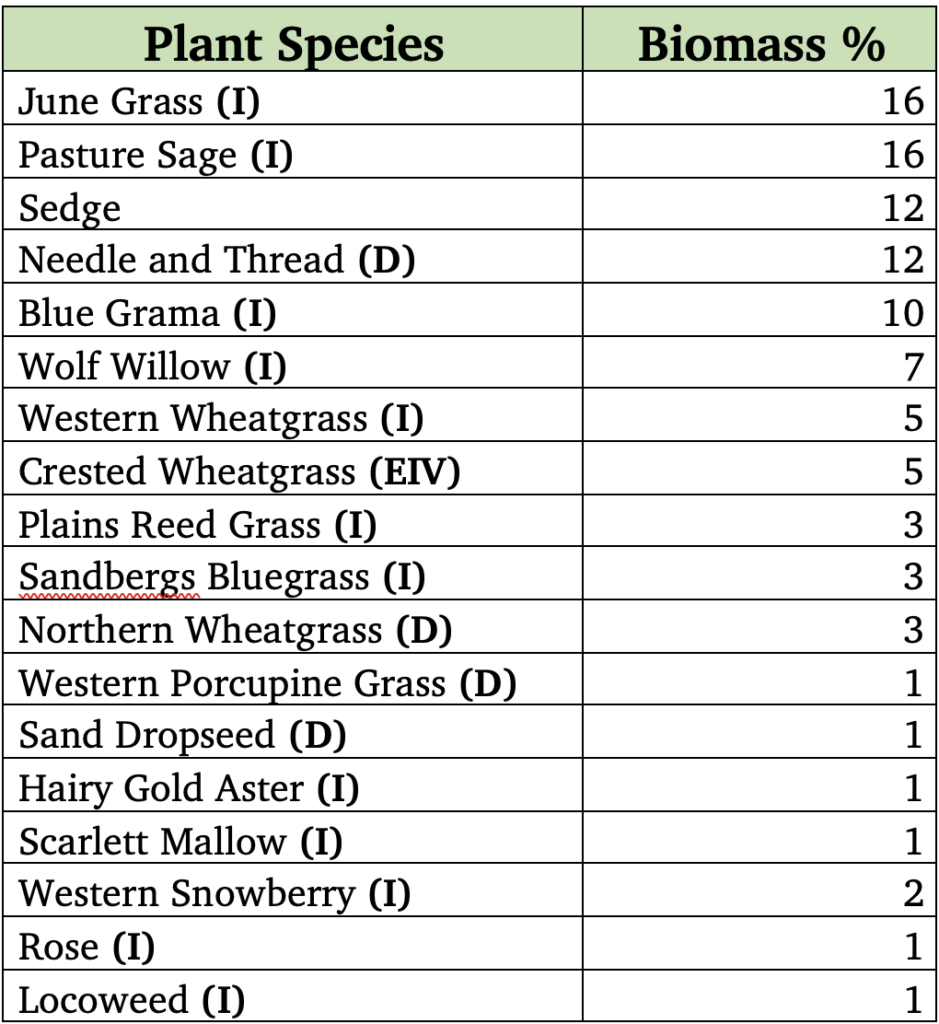

Here is an example of the same rangeland but under heavy grazing pressure and showing moderate alterations to the plant community.

We can see that the biomass percentages of decreaser species from the top community, like needle and thread, northern wheatgrass, and western porcupine grass have decreased, while the overall biomass of increaser species like june grass and pasture sage have increased. This represents a shift from a plant community made up of tall, productive, palatable grasses, to a plant community with lower growing, less palatable species.

The shift in the plant community species and their frequency show us that this rangeland is under stress. Communication with the landowner about the previous land use including grazing days, time of year and livestock density can also verify what we are seeing on the ground. It is important to note that the assessments we complete represent a snapshot of time on that rangeland and change can happen quickly so having a full history from the landowner of their strategies, challenges and any recent changes is crucial to get a better understanding of why we might be seeing changes.

At the end of the day, knowing your pastures isn’t just about putting names to the plants there. It’s about understanding what your land is telling you. When you can spot what’s thriving and what’s struggling, you’re better equipped to make grazing decisions that support both your herd and the health of your pasture.

Author: Mindy Hockley-Anderson